|

|

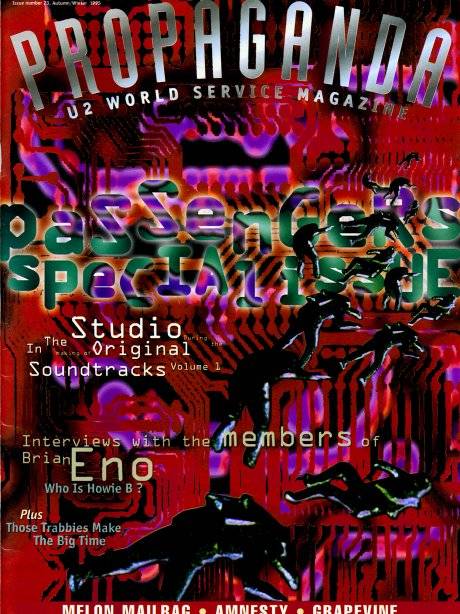

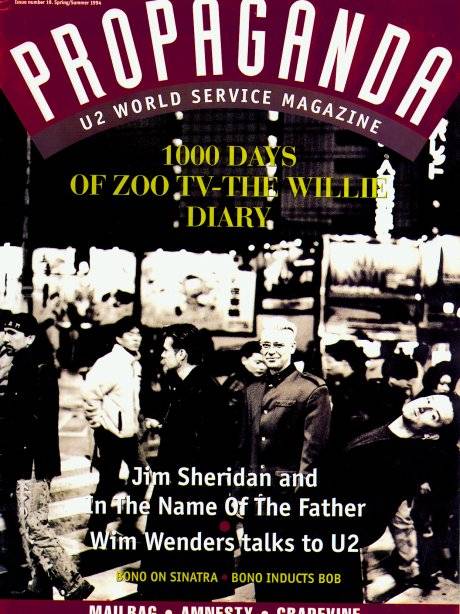

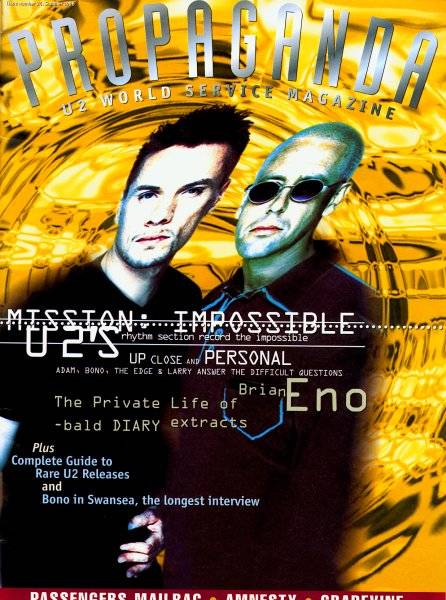

| Propaganda 23 |

|

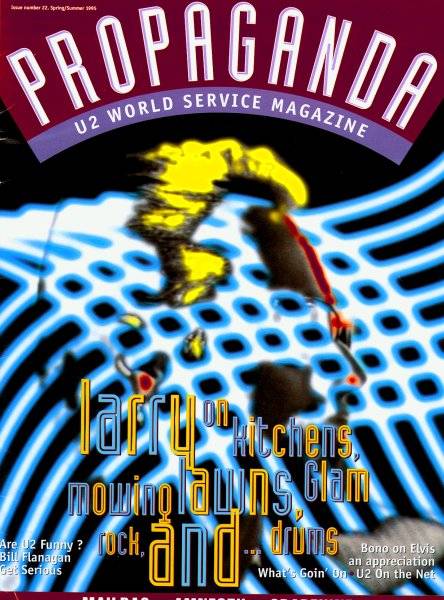

| Propaganda 22 |

|

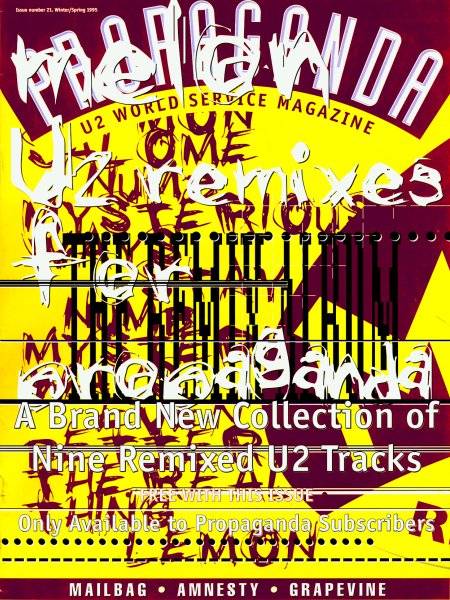

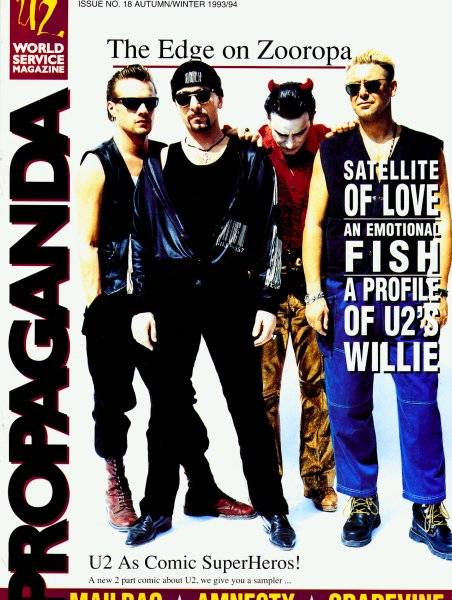

| Propaganda 21 |

|

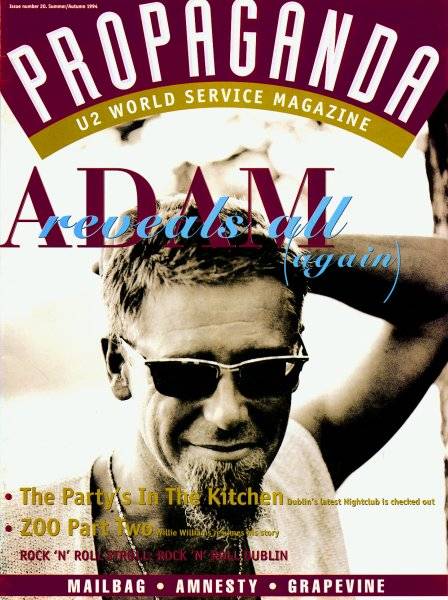

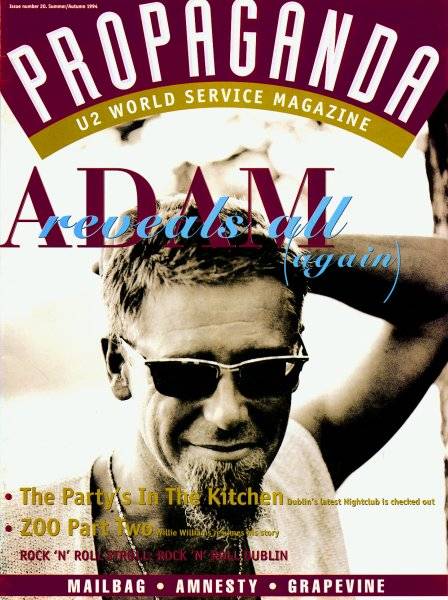

| Propaganda 20 |

|

| Propaganda 19 |

|

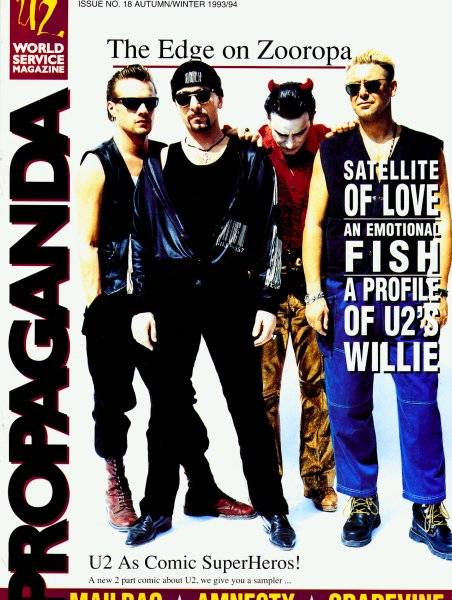

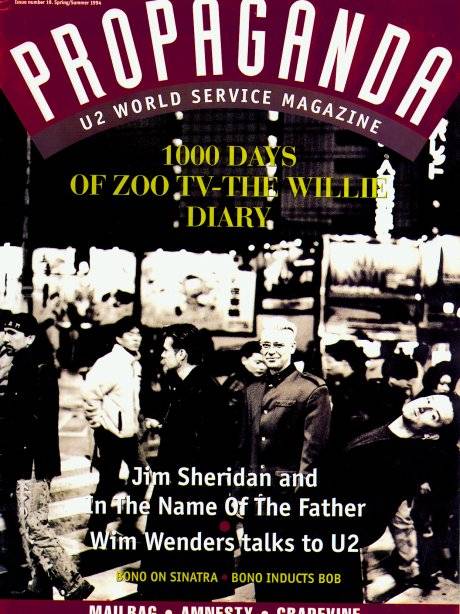

| Propaganda 18 |

|

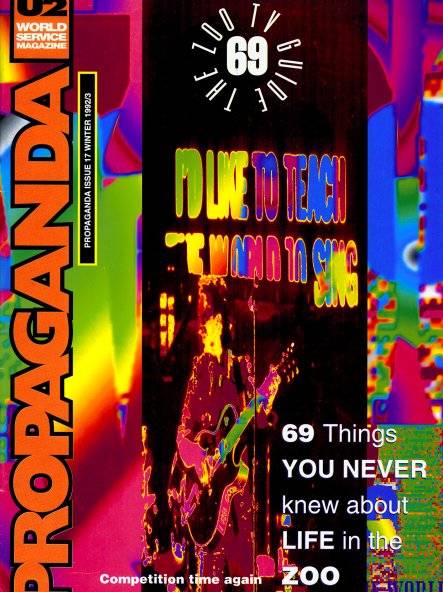

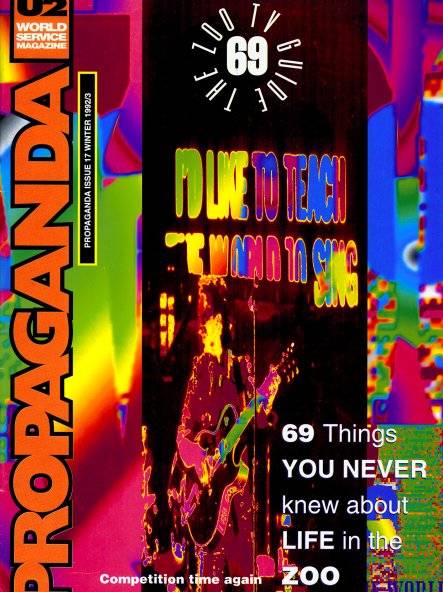

| Propaganda 17 |

|

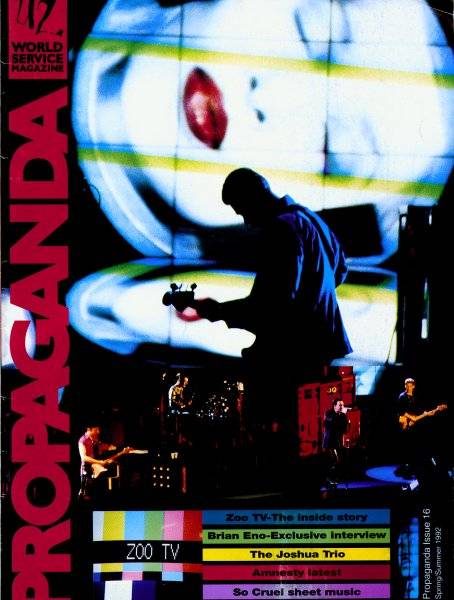

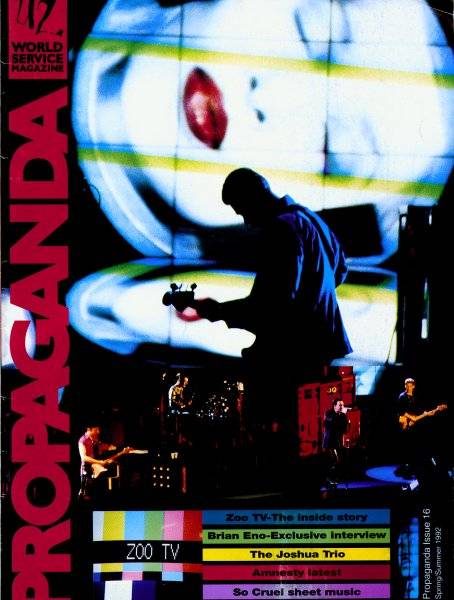

| Propaganda 16 |

|

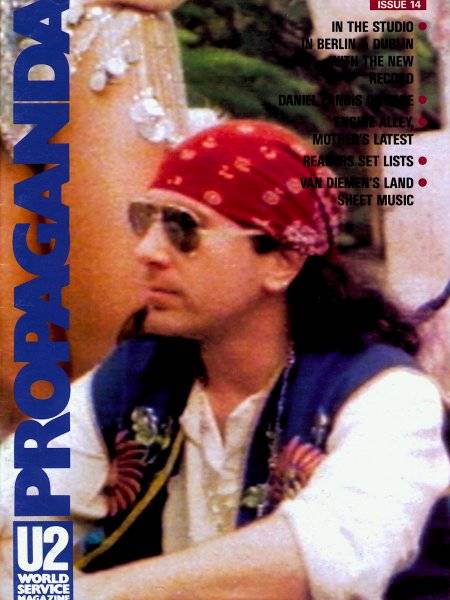

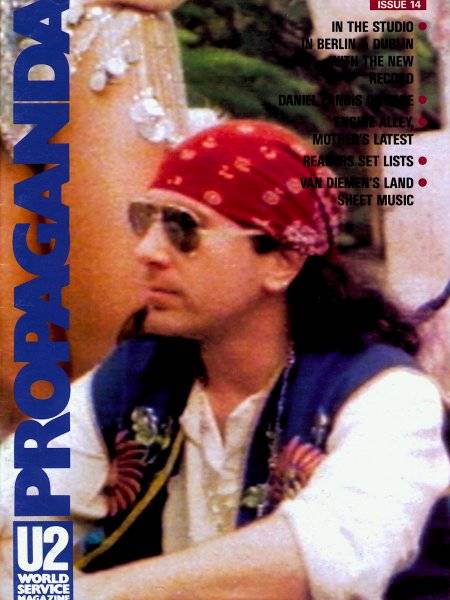

| Propaganda 14 |

|

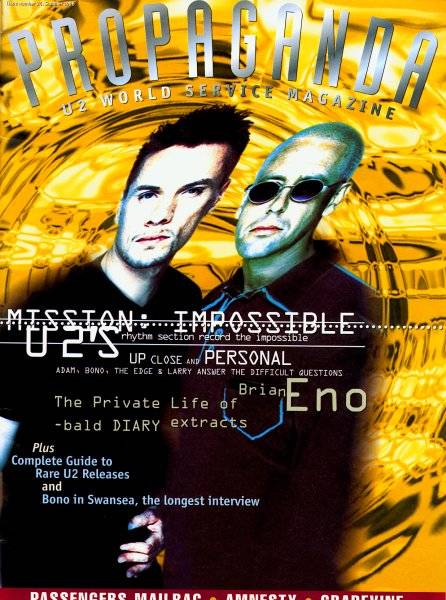

| Propaganda 24 |

|

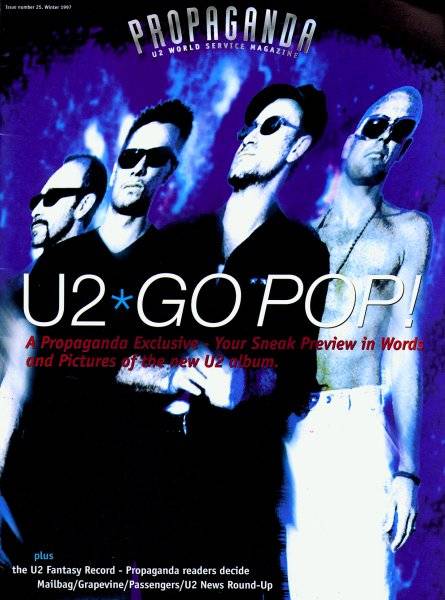

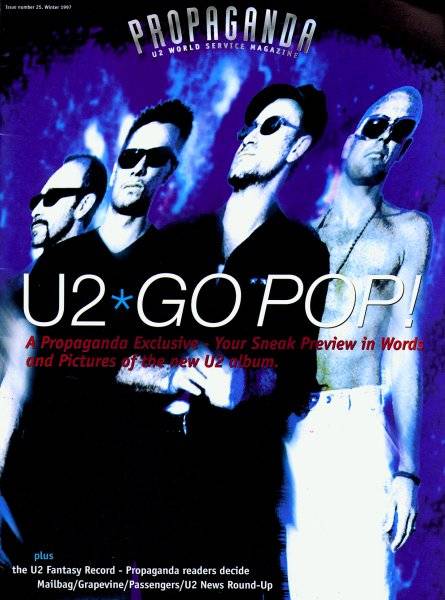

| Propaganda 25 |

|

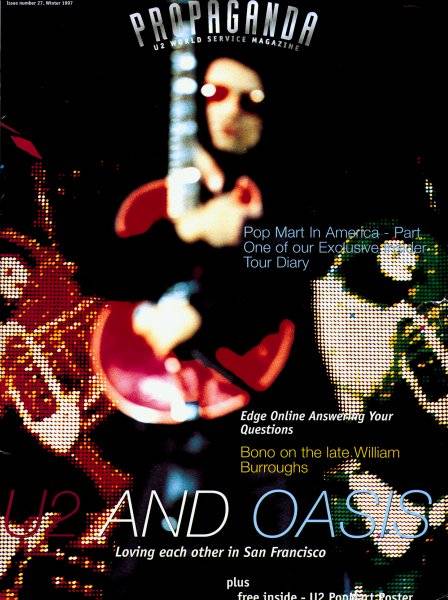

| Propaganda 27 |

|

| Propaganda 28/29 |

|

All Passengers Present and Correct - Propaganda, Issue 23 - Aug 1995

It is late July, a Wednesday. Dublin is hot. The members of U2 and the members of Brian Eno are in a recording

studio on the riverside, with a promise to finish making their joint album in three days. After that the members of U2 go

off on their holidays and the members of Brian Eno start to finish the music of what will be Your Blue Room - Music for Films

4. Except of course it won't be. But that was then and this is now. In between the Passengers arrived with Original Soundtracks

1. This is the story of a day in that studio.

12 p.m. Bono and Edge were at the studio late last night and they

are first in this morning. Edge is playing a synthesizer in the studio, writing a theme, so he says, for the new James Bond

film. Such is the purple patch that U2 are in at the present, that while they have only three days to finish off their soundtrack

album, Edge is writing a different piece which will not be on the album at all. Bono is wandering around the premises, allegedly

in search of a missing chord. Edge gave it to him last night but he has lost it already. "We've got 'till Saturday," says

the guitarist. "But we've got a few nuts to crack yet."

12:30 p.m. Bono is excited with the material that U2

and Eno have come up with. He tries to operate an intimidatingly big tape-machine in a bid to find the latest version of "Your

Blue Room," which they have written for a film that the legendary Italian director Michelango Antonioni started and their

long-time cinematic collaborator Wim Wenders is helping to finish. The track is for a love scene, an erotic scene, explains

Bono, chuckling at the idea of Wim Wenders directing it.

Edge arrives, wondering where that TV scene of the alcoholic

talking to the priest is. They're writing music for it. It's a scene from a new Phil Joanou film -- the man who directed Rattle

and Hum.

Brian Eno, fifth member of the burgeoning group of musicians making this record, is sitting in front of a

sophisticated Apple Mac computer and manipulating scanned images of the band into something that could become the album cover.

"There are a number of Brian Enos," explains Bono, "This is the artwork Brian Eno."

On two noticeboards in the room

are scrawled lines of song titles, most of which will have been changed before the album is released. At the foot of one board

reads the slogan, "Make the Music of the Future You Want To Live In."

Tokyo Drift Ito Okashi Davidoff Antarctica Fleet

Click Plot ISO Tokyo Glacier (Fact) Slow Star (Time) Always Forever

The early signs confirm the earlier ones -- it

was Japan at the end of the Zoo TV tour, which is where the record was conceived.

"For whatever reason, Tokyo seems

to be the home of this record," says Bono. "Arriving there at the end of the Zoo TV tour, it became clear to us that this

was actually the capital of Zoo TV. In Tokyo, you don't feel you are in the present tense. You feel as if you have stepped

into the future."

He pauses, recalling those final days of the Zoo TV tour at the end of 1994. "It's not all good,

but it is definitely not boring. I went to bed hardly at all. I just couldn't sleep, there was just so much going on outside.

We spent a lot of time in this area called Shun Shuku and Electric City, where you have these 25-50 foot neon signs in blue

gold, flashing messages and huge hoarding advertising manga movies and cartoons."

Looking back, it seems to the singer

that Tokyo was like a "waking dream," the strange mix of the Yakuza -- the Japanese Mafia -- riding around in bullet-proof

Rolls Royces, mixed in with the mundane humility and unending politeness of everyday folk in the city.

"We had to keep

escaping our minders -- because the promoter wants to take care of you -- to get into the dodgy areas of town. So we'd slip

out of the back door and disappear into the night just to meet people."

So, in a strange, slightly surreal way, this

latest U2-driven project was born in Tokyo, where the band felt like they had slipped into the 21st century or into Ridley

Scott's Blade Runner. "Something went off in my head," says Bono. When the bits came to ground, some of them landed on Passengers.

"Tokyo opened the next chapter for us," he adds.

It was a year later that the band were in the studio in West London,

experimenting with Brian Eno on abstract ideas and soundtrack possibilities. With videos of old movies and cartoons playing

on the monitor, something clicked.

"We would stick these videos on and play to them with the sound turned down and

the thing that came out to me was the sound of where we had been the year previously..."

1:15 p.m. Bono is waxing

enthusiastic about the experimental noises coming out of the speakers as he plays back some of the new material. At this stage,

three months before official release, it has some of the strangest sounds and most jagged noisescapes that U2 have ever featured

in. The plastic soundscapes of Zooropa have been warped ever further back into the future.

"A song doesn't have to

have a centre," says Bono. "In dance music it is the rhythm that is the centre. We are making music for movies and we're trying

to pull that off without seeing the picture."

Edge expands a little: "Often things are set up as instrumentals, but

at some point they just seem to turn into songs, which I think is lovely myself." The beautiful moving piece that is "Your

Blue Room" is playing back at full volume. Eno is yelling at the keyboard. Bono is yelling at the couch.

2 p.m.

Bono explains how he impersonated his dad Bob Hewson, impersonating an opera singer in the bath to lay down the operatic tenor

for "Miss Sarajevo." He had been approached by Pavarotti to write him a song. Bono replied that, while he felt this a great

honour, unfortunately he had no time at present. Pavarotti was undaunted. And he had God on his side. He said that he had

spoken to the angels and that Bono would be writing him a song and also singing at his autumn charity concert in Italy. Bono

said that okay, he could write him a song, but he was definitely not coming to Modena -- there was just too much going on,

not least recording an album with Brian Eno.

Luciano Pavarotti cannot even spell the word "No." To cut a long story

short, a deal was brokered. Pavarotti would sing the tenor part on "Miss Sarajevo" and Edge, Bono and Eno would play a couple

of songs at Luciano's charity gig in September.

"It's a beautiful song," says Bono. "Quite elusive, and sometimes I

think it overpowers us. Sometimes it's a breeze that blows in one window and out the other without you noticing."

3:30

p.m. A piece of music presently called "One Finger Piano" -- later "Beach Sequence" -- is playing and everyone is listening

to make comments. It is written for a scene in the Antonioni/Wenders film where John Malkovich is on the beach by a swing.

It opens with birdsong and the one finger is Bono's. The singer is murmuring a single vocal line: "Time...shoots by on" repeated

over and over.

Adam arrives through a window, with Anton Corbijn. They have been doing photos out at Adam's place.

Edge asks Brian what's happening next. Brian is lost in his computer screen.

4 p.m. Howie B. arrives from another

studio in Dublin where he has been up all night mixing tracks at U2-Eno's suggestion. Bono met him recently performing at

the Kitchen and promptly recruited him to the cause of the new album.

"Let me show you this Elvis poem I've got," says

Bono. "I wonder if you can do anything with this." Bono reads it rap style and Howie B. goes into the groove and can barely

be restrained from moving all over the floor. "Fuckin' mad," says Howie B. in his thick Glaswegian accent. "I've got some

stuff here from last night, Edge was fuckin' wild."

Howie B. plays the track back to Bono and Eno listens too, while

still making the front of the album on his computer. As the music plays Howie B. is bending and blowing like a devout Jew

on acid at the Wailing Wall. Bono is also grooving, thinking the "trip" fits the mood of the record. Howie B. is alarmed at

a rogue click, but Eno reckons he can get rid of it. "Thank fuck for that," says Howie B.

"We'd better go after that

Blade Runner soundtrack," says Bono, "that one would fit perfectly."

It's a bit long but that's no problem: "It'll

fade into something else," says Howie B. "It'll fade into any fucker."

Bono says it is perfect Million Dollar Hotel

material, a scene he describes where a train is arriving at an airport. "It's got a bit of Hawaiian style," says Howie B.

"Nineties

Hawaiian style," says Adam, who is pleased as Bono with what Howie B. has come up with, and they send him off with the Elvis

poem. Meanwhile, the search is on for something called "After the Jungle," or at least a version of this that everyone liked

-- and approved -- last week. "We could do another version," someone says.

"We don't want ninety-four fucking mixes

to choose from," says Eno, throwing his hands up in the air in mock theatrical horror.

Eno has a different kind of

role on this recording than in other U2 records. Adam explains: "As we let the chemistry of the sessions develop, we put Brian

in the role of choosing the material and deciding to what extent it needed finishing. We were really working under Brian's

instruction so when we had those pieces identified, we then brought up the rear with melodies and other ideas...the chemistry

has been a different one to a normal U2 record."

"Basically we made Brian captain," chimes Bono. "It's his ship and

we've made ourselves available."

Then a qualification: "At the same time it's not that simple, because we're a band

with a very strong identity and strong ideas about what we want to do -- so inevitably some songs, for instance, have appeared,

which were not part of the original plan."

But it's worked well: "It's not a U2 record, it's a U2-Brian Eno record,

so it's much better," says the singer.

Anton Corbijn, the band's favourite photographer, who is over to do a shoot

for the record's release, wanders over to Eno's screen to see how he is "ruining" another of his photos.

"What we need,"

says Anton, "is to get to the stage where we have the picture, and then make the music fit the picture."

4:45 p.m.

A track called "Tokyo Drowning" is being rubbed off the main whiteboard, no longer featuring in the future of U2, the future

of Brian Eno, maybe the future of anything. It has been played twice to the general lack of enthusiasm of the Passengers and

it has been found wanting.

A track called "Davidoff" goes the same way: "Can we say the same for this old stodge?"

asks Eno, not particularly mincing his words.

"Tokyo Drift" metamorphoses into "Different Kind of Blue," a memorable

song with the refrain, With the twilight breaking through, It's a different kind of blue." It's a low-key, laid-back number,

riding on a smooth bass line, but Captain Eno is characteristically unsentimental in his judgement: "I have to say, I think

it's a weak track..."

Bono: "I disagree, I really like it..."

Edge: "It's got that lazy, lounge lizard feel,

the only phrase I can think of."

Bono: "I like that lounge lizard thing."

The comments go round the room. Adam

can live with it. Larry is less sure, wondering how it will fit in the context of the whole album. Bono wants it played again.

This time round there is a slightly stronger feeling that it is not quite there, but that it is only missing something special

from being something special.

Captain Eno would be happy to lose it, but concedes that if it had a more "inter-planetary"

feel (Bono's phrase) then it could work. A "Different Kind of Blue" has hovered within an inch of the studio floor, but has

miraculously survived.

"Right, let's listen to 'Miss Sarajevo,' " says Eno.

"Which one do you want?" asks Bono.

"No Pav, Fake Pav or Italian Pav?" They go for Fake Pav, but the search for the Pav is to take the best part of two hours.

Bono explains that the lyrical idea behind "Miss Sarajevo" invokes -- and maybe undoes -- the spirit of the book of

Ecclesiastes, a "time for everything under heaven." But is there a time to finish this album?

Everyone leaves the green

room for the recording studio to hear the track on a different system. The opinions continue, getting more mixed as they go.

"It may seem a bit lazy," explains Larry. "But we've been in here quite a while now and we're getting a bit tired."

And

as this is the playback, it's down to everyone's opinions: "It's much more directive when we're actually recording."

It's

time for a break. Anton and a camera beckon.

6:15 p.m. While the set is prepared for the photo shoot, Adam talks

about the creation of the record, a process he has enjoyed immensely. It was last February that the potential of the ad-hoc

recordings seemed to become clear.

"We looked at the tracks and said, 'yes, they have potential, but we don't want

to get bogged down into a long project so let's look at the tracks where we can most quickly realise the potential."

It

was not going to be the next U2 album at this point? "The idea had always been for some kind of collaboration, depending on

the material that came out of it, but we were never quite sure what form that would take. Once we thought of it as a soundtrack

then it looked like a record that was a collaboration between the five of us."

Propaganda: Are there times when you've

thought, that track would fit on the next U2 record, let's keep it."

"In a minor sense. Some songs that look like they're

going to take a lot of time to finish, we've said we'll put them on the back burner. Those things may turn up, but it depends

on how much we material we generate. At the moment we've already generated about ten ideas for a new U2 record, but it will

be a long time before the character of the new U2 record will be decided."

Propaganda: Is there a different attitude

in making a record like this one?"

"Certainly, the attitude going into this has been, well, it doesn't have to be anything,

we can make it up as we go along; we found some songs along the way and we found some instrumental pieces."

A huge

Day-Glo orange painting has been erected in one corner of the first floor of the studio complex: the scene shows a tower block,

atop with Japanese hoardings, under a royal blue sky, with helicopters flying at the side and a cartoon mermaid sitting on

one wing. Within minutes, for some reason, Edge is walking around in a tweed suit, plus-fours, brogues, a floppy golf cap

and looking for all the world like a pre-WWII golfer. Not to be outdone, Adam is entirely got up as an airline pilot in dark

blue suit, cap, shirt and tie. Brian Eno is decked out as a chef, Larry as a biker and Bono as a bizarre Mexican revolutionary,

huge bullet-belt slung round his waist and all hidden under a monster sombrero.

"I have no idea what the idea is,"

says Larry, speaking for the entire cast. Eventually all five members of U2-Eno are lined up on the set and only Anton Corbijn

knows what he is up to. And shooting. The photo session goes on for days and days. Bono changes into a Hawaiian shirt-clad

holiday-maker look. Then all five members change into chef-wear and depart from the studio complex to walk down to the Liffey

where Anton has a further scene in his head. There is a certain surreal authenticity to the scene: drinkers in one of the

pubs lean out of the window and shout, "Beef curry and egg fried rice," unaware at just who they are making their mock orders

of.

The photos apparently come to nothing, but it's a good way to work up an appetite and by the time everyone troops

back to the studio supper is being served.

9:30 p.m. Howie B. is back again with some more mixes, and everyone

is listening to the lost version of "Miss Sarajevo" that the engineers have found. The scene continues as before, but this

time Edge, for one, feels like they are closing in on the object of their hunt, that the endgame for the Passengers beckons:

"We were a million miles away earlier on today, but now it feels like it's getting there." For another two hours the Passengers

listen to tracks and argue their merits.

11:30 p.m. Bono, loungin' on a settee while the others continue to

playback, talks about Original Soundtracks. There's a lot of air and space on some of the more ambient material, almost reminiscent

of Boy. The singer jumps at the word "space."

"Space, see, that's the hardest thing of all," he enthuses. "That's one

of the reasons we picked up on Howie B., because his mixes have a lot of space in them. Density seems to be the thing of the

Eighties, but air is of the Nineties."

He too, has found the concept of making music for films liberating -- even when

the films don't exist. "Soundtracks are a great place to experiment, to find sounds and musical ideas that are not pinned

to traditional song structure ideas," he explains. "Even people like Ennio Morricone formed little experimental groups from

which they would make discoveries and then bring them back to their mainstream.

"Before we did Achtung Baby, myself

and Edge worked on A Clockwork Orange, and you start to see things in different perspectives. You can formalise those ideas

later, but there is an excitement in the raw when you first make them, so we decided to put out a record that was like that."

He

explains that some of the songs from the West Side studio sessions in November '94 have "sprouted" and "turned into songs,"

which will not be on the Passengers work, but on the next U2 record. That, he says, is going to be a "rock record." "This,"

he adds, with a wink, "is just getting the art out of our system."

Propaganda: "So what kind of album do you think

Original Soundtracks is?"

"We've always wanted to make what you might describe as a blue record, an ambient record,

an atmospheric record.

"People listen to records for a reason, there's a function. Even though often musicians don't

like to believe this, people play their records at certain practical times -- like going out or going on a long drive -- and

U2 hasn't yet made an After Midnight record. I thought it would be nice to have such a thing in our collection."

It's

pretty late at night as we speak, after a hard day's work in the studio. But Bono is not tired yet, indeed he is warming to

his theme.

"None of us in U2 want to make music that you can eat to," he says. "We want to make music that you can

have sex to. Dinner party music is never going to be our thing...

"It's a chill-out record in club scene terminology.

We'll make the record spikey towards the end so that people can take it off, they won't be able to fall asleep to this."

12

a.m. While some U2 fans may find this record an experiment too far, others, says Bono, will find it an exciting new departure.

"Our

audience has proved to be very elastic over the years and Zooropa certainly pushed it. There are very few guitars on Zooropa

and we used a lot of very plastic sounds and video arcade noises.

"This record is going even further, but it is connecting

with what is going on in club culture where people are tired of safe dance rhythms and easy tunes. They are looking to be

poked a little as well as seduced."

Which is what he fancies a little of just now himself, getting up and inviting

all and sundry to the Kitchen for a little late night club action. Does this man never tire? Edge, meanwhile, has gone off

to do some photography with Anton, Larry is watching telly and the last word on this day and this record is left to Adam.

"We're

going to put out the record and see how people react to it. It's probably best to view it (Passengers) as a completely separate

project, but it has been great fun and it has meant that we've done creative work this year to get ourselves into shape for

the next U2 project. It's been an adventure for us."

© Propaganda, 1995. All rights reserved.

|