|

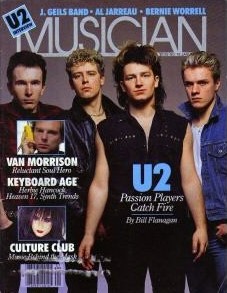

MUSICIAN // Jan 1985

Soul Revelation And The Baptism Of Fire

Musician, January 1985

by: Bill Flanagan

When Paul "Bono" Hewson was in the Irish equivalent of high school, he decided that the compulsory study of Gaelic, the

ancient Irish language, was foolish. "Being the obstreperous little git that I am," U2's singer/lyricist explains, "I refused

point blank to do it. I would bring German books into Irish class just for the sheer hell of it. When a major exam came, I

didn't pass. I burned my papers outside the exam hall. I was pretty hardheaded and I thought, 'This language is dead. Why

am I learning something that's dead?' I went to university after that, and I was thrown out for not speaking Irish."

Now

that he's a world-famous rock star, Bono has second thoughts about that dead language. "The reason it's dead is because many

generations of people killed it. And I was one of them. I have completely come around. It was me that was missing out. Irish

poetry brought me around. There are sounds in the Irish language that aren't there in English. Having rebelled against it

for so long, right now I'm very interested in the Irish language."

The story is vintage Bono, at once self-righteous

and self-deprecating. Who else would take such delight in recounting how bold and stubborn he was, only to conclude that he

was also completely wrong?

We're sitting backstage at a concert hall in the south of France. For several days Bono's

expertise in French has helped us navigate strange rues and order in restaurants.

"I'm interested in German

and Spanish," he offers. "I find Spanish one of the easiest languages. 'If the Englishmen hoard their words like misers, the

Irish spend them like madmen.' I have a lot of African verse at home, Indian verse, French verse. When a melody comes to me,

it comes in sounds. I have to sort through the sounds to find the words. Sometimes I'm left with a big hole where no English

words will fit. So I have to find other words."

Bono resorts to what sound like Indian syllables in the middle of "Elvis

Presley and America," a song from U2's new LP The Unforgettable Fire. Some listeners might not notice; the whole song

is a moody mumble that -- while sounding nothing like any record Presley ever mad -- captures a piece of his spirit. "Elvis

Presley and America" is about reconciling apparent contradictions: joy and despair, genius and inarticulation, humble Christian

continence and boastful rock abandon. It’s split right down the middle. It's typical U2.

Bono's been keeping

fast company. He and Van Morrison joined Bob Dylan onstage in Ireland recently. Bono dislikes talking about it, but a friendship

between the young singer and Dylan seems to be blooming. Dylan and Morrison believe in the muse, that songs come through the

singer from somewhere else. Does Bono feel that way about his own work?

"It feels like the songs are already

written," he smiles. "But our songs are too human for me to be so arrogant as to claim that they were written in the air.

I do believe the musician doesn't own the music, that it is a gift. I believe it is a gift of God -- to any musician: guys

on the street, traveling musicians, tinkers, gypsies. Music expresses the inexpressible. All our songs are about that, about

inarticulation: 'I try to sing this song.' 'Elvis Presley and America' is just a mumble. All are about trying

to express things."

U2'S ONSTAGE AND Bono's screaming, "TOU-LOUUUSE! TOU-LOUUUUSE!" The young people of Toulouse,

France, some of whom speak English, go wild. Dave Evans, the guitarist everyone calls the Edge, manages also to cover piano,

lap steel and synths, filling in all the dynamics a U2 record captures with many overdubs. Drummer Larry Mullen kicks the

band's spacier songs into the material world, and occasionally tosses in a Led Zep change-up. Bassist Adam Clayton drifts

in the sonic space between the Edge and Larry, sometimes adding aural shimmer, sometimes popping strings to hit the beat on

the head.

Afterward the band piles into their tour bus. The Edge sits back and closes his eyes. Mullen asks where Dennis

Sheehan, the road manager, is. "He's outside giving those girls your birthdate," the Edge lies.

"He's not!"

"Yes

he is." The Edge doesn't move a muscle. His eyes remain closed. But a smile crosses his mouth. Sheehan climbs on the bus and

Mullen, now sullen, demands to know if he gave those girls his birthdate. Sheehan goes along with the gag and says yes he

did. Mullen gets more upset. The girls, it seems, are witches.

"They're making voodoo dolls of you, Lawrence," the

Edge deadpans. "They're going to bite the legs off the dolls!" pipes up Bono as he climbs aboard. Like Larry and Edge, he's

an evangelical Christian who doesn't dig witchcraft.

Adam Clayton is not twice-born. He boards the bus smoking a cigarette

and drinking a beer. "I don't know why I'm never recognized," he announces. There is laughter all around. "I saw two girls

waiting by the bus and I thought, right, I'll give 'em a good chat. And they ignored me!"

"A prophet without honor,

Adam," Bono judges.

The Edge opens his eyes a slit and tells Bono, "Those two witches were outside looking to make

a voodoo doll of you."

"Not the same two who were at soundcheck?"

"Yes. They've already got your birthdate."

Bono

sighs. "Then they must be sticking pins in their calendar." The shade Bono's leaning against flies up, causing the fans outside

to jump and wave. "Their magic is working already."

U2 HAS RUN into trouble before, but it hasn't impeded the band's

steady progress. The four Dubliners got together as teenagers in 1976, attracted by a notice Mullen posted in school. After

gaining a local following they signed to Island Records in 1980 and released Boy, an album that sounded like guitar-rock

drenched in echo and sent for a spin-dry in the Twilight Zone. While the Edge, Clayton and Mullen flailed away, Bono intoned

lyrics evocative of adolescent moods and yearnings.

The group's follow-up album, October, now appears as a lesser

work. Mitigating circumstances: Bono's lyrics were stolen during a U2 tour, and the singer virtually extemporized what's on

the record. War, 1983's studio release, solidified U2's reputation as a band with a conscience; Under a Blood Red

Sky, a subsequent live mini-album, consolidated it. U2 wasn't just loud -- they were stirring.

The Unforgettable

Fire lunged up record charts with all the momentum of a band at peak form delivering what the fans want. But tell Adam

Clayton that the record bears two or three potential hit singles and he'll reply, "I hope not."

That calls for explanation.

"To release 'Pride' and have a hit is great," the bassist says. "But I don't want any of the other songs out. The album's

important, not the singles that come off it. I'd like it to be viewed as a whole, rather than as 'that album with three hit

singles.' I'd like the albums to dictate the way people think about us.

"There is a feeling within the band of consolidating

and working material through a sort of 1984 soul music. In the way that Springsteen is soul music, but it's rock 'n' roll

soul. Van Morrison is soul music. In the past our live shows had to rely on songs that impressed people, because we

weren't very well known. Now we have the freedom to expand the whole concept of the band and the songs. We don't have to fight

to grab people's ears anymore. We've got them."

"To me," Bono offers, "soul music is not about being black or white

or the instrument you play or about a particular chart or map." We are seated in the back of the tour bus. Outside the fields,

vineyards, castles and farms of southern France are flying by. "A singer becomes a soul singer when he decides to reveal rather

than conceal. When he takes what's on the inside and brings it to the outside. I suppose," Bono smiles, "that what I take

from the inside is a little more tangled up than most people. So it may not communicate as directly as Bruce does. I'm in

awe of the way Bruce Springsteen can communicate directly with people."

A lot of Bruce/Van soul comes through on U2's

new album. When Bono steps out under a white spotlight to sing the first lines of "Bad" over chiming, ethereal music, it's

hard not to think of the opening of "Thunder Road" or "Backstreets." But Unforgettable Fire's sound is not that of

"Born to Run" or "Domino," let alone the straight-ahead rock 'n' roll of War and Under a Blood Red Sky. It's

an introspective dream like "Listen to the Lion" or "New York City Serenade."

Last year's War and the live Under

a Blood Red Sky were straight-ahead rock 'n' roll statements that earned U2 a big American audience.

"There's got

to be a spiritual link between U2 and Van Morrison," Bono nods. "And I'm sure it's not just that we're both Irish. I think

there's something else. He probably wouldn't want to associate himself with our music, 'cause I know he's plugged into a tradition

of soul music and gospel. He may not connect with us."

U2's new record has a song called "4th of July," just as Morrison

has his "Almost Independence Day" and Springsteen his "4th of July, Asbury Park." But the spiritual connection is most obvious

on "Promenade," a lovely song about watching rockets explode over a seaside town that ends with Bono intoning, "Radio, radio,

radio, radio."

Bono says most of "Promenade"'s Van/Bruce connections were unconscious. He was describing a real place

in Ireland. "The song was written in one take. I went to the microphone with a piece of music and just sang it. In some ways

it's complete coincidence. The 'radio' image just came to me -- and obviously I turned it into that Van lick: 'Radio, radio,

radio.'

"I know some people have problems with the gray area of the lyrics, but after coming from the black and white

of War I wanted to retreat into the gray again. The emotions that are on this record are very abstract, out of focus,

fragmented, its words are gray. But that is exactly what it should be.

"It just seems that in 1984 in pop music,

in rock 'n' roll, everything is spelled out. There is no mystery, no attention to the magical side of music. If there's one

thing I re-learned from working with Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois it's that music is magical. It is not a production line.

Americans have to watch out for this, because there's a very strong music industry in the United States. Some people in that

industry talk a lot about formulas. Radio's divided into AOR, CHR, R'n'R, R&B. There's a danger of people thinking in

terms of platinum and gold. This record is stepping back from that."

U2's War featured a straight-ahead guitar/bass/drum

approach and headline lyrics (heavily influenced by John Lennon LPs like Some Time In New York City) in reaction against

the high-gloss pop mood music then dominating the British charts. They couldn't anticipate that the album would make them

trendsetters, leading a stampede of hearty guitar bands like Big Country and the Alarm. What U2 did was nothing less than

channel the unharnessed energy of guitar-based power-rock for a more constructive message than the usual sex 'n' drugs 'n'

rock 'n' roll bill of fare.

"There are few instruments that get across aggression as well as a distorted guitar," Bono

said in a 1983 interview; "it's physically brutalizing. The power of a rock 'n' roll concert is that it stimulates you emotionally,

as you follow the singer, and physically, as you dance and are hit by the music. It also has a cleansing effect; it's a great

release.

"The brutalizing effect of guitar has been used in a very negative direction at times. But our aggression

is much warmer, much more communicative than that."

Nowadays Bono has a little perspective on what U2 hath wrought.

"We didn't now that we'd be at the front of a whole movement of guitar and optimism," he sighs. "When that happened

we had to step back and redress the balance."

"It's difficult to handle," the Edge says of U2's new vanguard status.

"We never intended to become part of a movement. Movements can be very restrictive. Very early on we were linked with a whole

psychedelic revival. Now in the States it's this Positive Vision movement -- the re-emergence of the guitar and that sort

of thing. Whenever we felt on the verge of becoming a caricature of ourselves we've always done something different.

"This

whole idea of the new guitar bands, the new guitar heroes is terrible. But I would be proud to be thought of as in

the same genre as Simple Minds, simply because I think the uplifting quality they have is so great."

"The Unforgettable

Fire" was the title of an exhibition of paintings by survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Obviously U2 are also conscious

of the title's invocation of the Christian Pentecost, the baptism of fire in which the Holy Spirit entered the apostles.

But

The Unforgettable Fire mostly refers to obsessive passion. "Pride (In the Name of Love)" and "MLK" find this passion

at its greatest in Martin Luther King. King, after all, was a charismatic, powerfully articulate, righteous Christian pacifist

-- all that Bono admires exemplified in one man. That the fire has two sides, consuming as well as liberating, is explored

in "Elvis Presley and America." That song's protagonist, Bono explains, "was unsure of himself intellectually when he should

have been sure! Elvis could say more in somebody else's song than Albert Goldman could say in any book!"

Bono says

he writes his lyrics instinctively, and only later discovers what his songs are really about. He admits he's just realized

that "Bad" and "The Unforgettable Fire" are both partly about that darkest passion, heroin. The drug has found a sizable market

among the melancholy Irish, and U2 are finding old friends with holes in their arms.

"I'm not saying that's what those

songs are completely about," Bono says carefully. "I don't want to tie them down. Not having been a junkie I didn't want to

write about junk. But I suppose, living on the street where I live, seeing people that I've kicked football with have their

lives rearranged by this love of a drug, it just seeped subconsciously into the record."

Might Bono also have been

writing about how his old friends now see him? For he too is a man changed by obsession: obsession with music and obsession

with the Divine.

"I suppose that I've been musically obsessed," Bono says slowly. "I don't know. I'm not clear. I only

share these thoughts with you because I'm starting to become clear on those. I'm sure I'll learn a lot more as we play

the songs."

AS THE BUS pulls into Bordeaux, Bono inserts a cassette of Springsteen's Born in the U.S.A.

and rocks down the aisle. Driving into a stately old French city, a bunch of Irishmen affect American accents to sing "Drivin'

Into Darlington County." At the next concert Bono will first sing U2's "Gloria" and then Van Morrison's. The rock 'n' roll

nation recognizes no boundaries.

These French concerts, performed to crowds of eight or nine thousand in sports arenas,

are the best U2 shows I've ever seen. The band's early club dates were exciting but suffered a bit from lack of dynamics:

Boy's songs were of a single mood, and the group lacked finances to get a variety of sounds from one guitar, bass and

drums.

Later American shows, especially some concerts last year in big halls, benefited from three albums' worth of

material but ran into an unexpected problem: Bono's distracting penchant for excessive showmanship. He leapt into audiences

and scurried up balconies. Kids went crazy and U2 fans understood the communal motivation behind the broad gestures. But the

half-converted were often appalled.

As a U2 fan I often found myself defending the group against charges of bombast,

of egomania, of being a hip Journey. I remember the look of astonishment on one musician's face when he saw the "Sunday Bloody

Sunday" video: "This guy is marching up and down the stage waving a flag!" Something was getting lost in the translation.

It's

a great relief, then, to find Bono staying onstage in France and letting the music do the talking. U2 shows, which once came

on like frontal attacks, now move in waves; the level swells, falls and swells again.

"It was very important for Bono

to realize he didn’t need to do all that," Clayton says of the onstage antics. "By now we're playing for people who

already believe in the band. They just want to see him perform the songs."

"It was also," the Edge adds, "a gesture

that made sense to the front row. It was Bono saying, 'I can get to you, I can be with you.' But the cynics at the back of

the auditorium said, 'That's a bit cornball.' Now we're turning our eyes to the cynics, to the world-weary music fans, nonmusic

fans, and critics as well. We're approaching them in a more subtle way. We'll be communicating directly through our work.

I'm excited about that prospect."

"You can't fill a large stadium physically," Clayton adds. "You have to fill it with

music."

Bono remembers his partners' reaction to his onstage exhibitions: "I was getting phone calls from the band

after concerts -- phone calls at two in the morning where I'd have to go in and face a court martial. They were saying, 'You're

either going to kill yourself, or somebody else, or the band.'

"In the Los Angeles [Sports] Arena I went into the crowd

with a white flag and it was torn to pieces. I ended up in a fistfight with a member of the audience, which is a real contradiction.

Then I half fell from the balcony. It started a bit of a riot. [L.A. Times critic] Robert Hilburn wrote, 'The music

doesn't need this.' And he was right."

But Bono still feels strongly that if his methods were wrong, his intentions

were right. He wanted to break down the barrier between performer and audience, to raise a white flag as a gesture against

division, against nationalism, against war. When he sang "Surrender!" he meant everyone should refuse to kill for any flag.

The problem is that onstage Bono resembles less Gandhi than a charismatic figure demanding his arena -- full of fist-waving

fans surrender -- to him.

Bono looks shocked at the suggestion. "The principle of 'surrender' is both political

and personal," he explains. "I also meant it as dying to your ego.

"There are two types of musicians. Some people

I meet put in their cassette and say, 'Listen! Aren't I somethin'?' Others go, 'Listen! Isn't it somethin'?'

I suppose I have those two people in me, and I've been trying to shake the first one off.

"People in the band seem

to think I'm an odd combination of a person who doesn't believe in himself and a person who believes in himself too much.

I'm like anybody else; I'm a mass of contradictions. I just try to be myself. And most of our songs are about failure in that

respect: 'I fall down.' It's a lot more about picking yourself up from the dirt than about standing there with hands held

up, triumphant. But the songs themselves are not like that. I can’t be seen as any kind of spokesman. I mean, how can

you be a spokesman if all you're saying is 'Help!' "

"When we started playing," Clayton explains one evening, "music

was very much the secondary thing. We liked each other and got a lot of fun out of it as a social situation. Now we realize

that individually we probably wouldn't have gone anywhere musically. We enjoy the people we're with and realize that without

any one of us the fragile uniqueness and specialness of U2 would be gone forever. It's an idealistic approach to music. We

have rows; everybody who lives together has rows. But they're always rows based on the belief of what we can do, where

the music's going."

"The band is a family," the Edge adds. "Everyone looks after everyone else and no individual ego

is bared to the public. There's a band ego, there's a band ambition. There's a band arrogance as well, sometimes.

And there's also a belief that contemporary music can be more than just a soundtrack. It can be worthwhile and lasting, with

a timeless quality when it's really working. It should transcend any barriers of time or location, so anyone can find something

in it, so that it doesn't exclude people by being too fixed in its context. A lot of pop music is very fixed. It only

makes sense if you know what happens to be hip in New York or London that week. I'm sick of music like that."

ON

SUNDAY U2 has a night off. While Clayton stays in bed, recuperating from an especially late Saturday, Bono, the Edge and Mullen

explore Bordeaux. The ancient city seems to stretch out for miles in every direction. Narrow, winding streets open into great

cathedral squares before zigzagging down to the river. Walking avenue after avenue, U2 comes to the moving lights of a carnival,

stretched out in front of a great fountain and bathed in the glow of the biggest Ferris wheel they've ever seen.

Bono,

the most recognizable member of U2, has tucked his wild mane into a tight painter's cap. He refers to this as his "nerd disguise"

and looks like a Robin Williams character. It serves him well until the group comes to the shooting gallery. Everyone gets

pellet rifles except Edge, who for some reason is given a .22. As Edge splinters wooden targets, Bono, excited, yells over

the recoil, "Yeah, Edge! Go, Edge!"

That lets the cat out of the bag. How many young men in Bordeaux are named "Edge"?

And how many speak English? French kids start turning and pointing to the Irishmen at the shooting gallery. "Ur Dur! Ur Dur!"

("U Deux": "U2" en francais).

"Ur Dur?"

Mullen shakes his head no and the band moves quickly down the

midway. Bono spots a tent promising oddities of nature and zips in, leaving Mullen and the Edge outside.

Suddenly all

the fun goes out of the fair. Lined up before him are glass jars containing monkeys, mummies and human fetuses in formaldehyde:

Siamese twins, a human baby with a fishtail sewed on. Bono's face goes gray. In the midst of this depravity sits a dwarf in

a three-piece suit, cleaning his fingernails with a knife. He never looks up. Around his feet the dirt is littered with centimes.

Bono

walks, as if asleep, outside where Mullen and the Edge are laughing. Finally he says softly, "I've never seen anything like

that in my life." The park P.A. is blasting "Pride (In the Name of Love)." As we leave the carnival a barker is shouting into

a microphone, "Ur Dur! Ur Dur!"

At the next night's concert U2 performs "The Unforgettable Fire," a song that describes

"Carnival/the wheels fly and colors spin/through alcohol, red wine."

Bono speaks to the crowd: "When we reached the

top of wherever we were going -- with the War record and Under a Blood Red Sky -- we felt we had to make another

statement.

"Last night we came into Bordeaux. We walked around the city and we came to this carnival. There was this

big wheel at the carnival. We got on and we went right up to the top of it. We could see all over this city, Bordeaux."

The

kids cheer and then sit transfixed. The carnival was a wild mix of good and bad, but Bono is making a symbol of something

beautiful.

"So often we don't get to really see a city. Sometimes when you're travelin' a lot, you're goin' in and

out of hotel and hotel, another room and another room, more people and more people. You just forget that..."

He pauses.

"We have a pretty good job, actually." The crowd cheers and the band smiles. "This is for some of you who don't feel so good.

I'm sure you will."

© Musician, 1985. All rights reserved.

GUITAR PRIDE:

Bono unleashes his primal howl through a Shure SM58 vocal microphone. The Band's PA is by Clair Brothers

audio.

The Edge has a lot of guitars these days: A 1971 Fender Strat with a graphite nut, brass bridge

saddles, modified Seymour Duncan quarter pound stack pickup and Strat Tremolo. More standard are his 1971 Gibson Explorer,

an early-60's Les Paul Deluxe (used only on "Indian Summer Sky") and a 1961 Telecaster. He also plays a new Washburn acoustic.

On "Pride" he playes a 1959 Gretsch Falcon, with stero pickups he rewired to mono. He also uses an Epiphone Elektra lap

steel (1939 or 1940) which he picked up real cheap in the U.S. His amps are an old Vox AC30 and Mesa Moogies, MK-II C series.

His lap steel and Yamaha CP70, though, go through a Roland JC120 amp. His strings are Superwound Selectras.

He selects his effects with a Boss SCC-700. These include two Korg SDD-3000 Digital Delays, a Yamaha R-1000 digital reverb,

an MXR pitch transposer and a Yamaha D-15 digital delay. There are also two Electro-Harmonix Memory Man analog delays: one

side is used for the CP70, the other for the lap steel on "Surrender." He uses a MXR Compressor and thanks the Lord for his

Boss TU-12 tuner. What would you do if you had so much guitar equipment? How about taking up keyboards? The Edge did; he poinds

a Yamaha DX7 and CP70, and Oberheim OB-8 and DSX.

Adam Clayton plays a Fender Precision, Ibanez Musician and Fender Jazz bass through an Ampeg SVT bass

head (usedjust as a pre-amp) and four Harbinger cabinets with four 15-inch Gauss speakers. He uses JBL 2410 high frequency

drivers, two BGW 750B's and a BGW250B. That's not all. What about that Furman parametric equalizer and two-way crossover?

And dig those Moog Taurus pedals hooked to a Boss SCC-700 effects selector, Ibanez UE 400 and Ibanez HD 1000 digital delay!

All of this rigged up to two Alembic pre-amps. Fredom of movement? Clayton has plenty courtesy of a Nady 700series wireless

system.

Larry Mullen Jr. plays Yamaha drums, the Power recording series. He uses a 24-inch bass drum, a 14-inch

rack tom, two 16-inch floor toms, one 18-inch floor tom and a 14x6.5-inch snare. he has two piccolo snares - one by Ludwig

and one by Eddie Ryan, an Irishman who runs a London drum shop - and two Latin Percussion timbales. His cymbals are Paiste:

a 2002 18-inch crash, two Rude 18-inch crashes, one 20-inch Rude crash, a 20-inch 2002 Chinatop, and a pair of 14-inch Sound

Edge hi-hats.

Mullen uses all Yamaha hardware, Evans drum heards (usually Black Golds), and sticks designed by Cappella Wood in New

Jersey. He occasionally uses a Simmons SDS7 triggered by hsi acoustic drums. He uses a click track (triggered from Edge's

Oberheim DX) on "Unforgettable Fire" and "Bad".

|