|

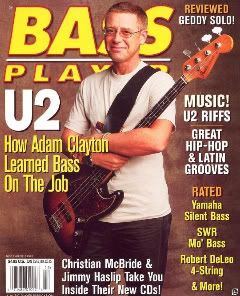

Adam Clayton: Stage and Studio

|

|

BASS PLAYER - Nov 2000

Reluctant Rock Star: How U2's Adam Clayton Learned to Play -- and Conquer the World

Onstage Bass Player, November 11, 2000 Gregory Isola

Somewhere between Bono (the world's biggest rock star),

the Edge (the world's coolest rock guitarist), and Larry Mullen Jr. (the world's baddest rock drummer) stands U2 bassist Adam

Clayton. "I just keep the bottom end moving," shrugs the affable 40-year-old. "I'm right on a good day, but there are so many

great cats out there. Really I'm just glad to be in the club." The release of All That You Can't Leave Behind marks two decades that U2 has

been in the bona fide rock star club. But while other top-drawer rockers learned to play in bedrooms and dank bars -- before

friends and forgivable fans -- Clayton's evolution as a player took place on the world's biggest stages. Of course, superstardom

was never the point. The three Dublin schoolboys who answered Mullen's ad for bandmates really just wanted to see what it

was like to stand onstage and bash out three-minute songs -- and they were terrible. That is, until they started writing their

own songs. "Even up through our first few records we got by on very little, at least musically," Clayton grimaces. "But we

were always able to make something of it, just in the way we played together."

U2 created an unprecedented blend of stark, post-punk instrumental textures, spiritual

lyrics, and over-the-top bombast that resulted in some of the most majestic rock music of the 1980s and '90s. Along the way,

Clayton went from struggling to hold together simple eighth-note grooves to incorporating bass influences from Motown to reggae

into his ever-evolving style. As elemental riffs like "With or Without You" and "New Year's Day" gave way to the Jamerson-style

bounce of "Angel of Harlem" and "Sweetest Thing," Clayton quietly became one of rock's reigning bass heroes -- whether he

knows it or not.

BP: Many see 1983's War as a breakthrough for U2. You in particular became

a distinct musical voice.

AC: On the early records, it was really just a case of Edge and Larry struggling

to keep the whole thing together. We were all surviving on minimal technique, and the formula in those early days was 4/4

bass over a relatively complex beat from Larry, with Edge doing his arpeggios over the top. But by the time we got to War,

the songs were more structured, and the bass sound was featured more. Also, I suppose by then I could actually play things

in time -- and in tune -- so I was able to be a bit more melodic.

BP: "New Year's Day" remains your most famous riff.

AC: That actually grew out of me trying to work out the chords to the Visage tune

"Fade to Grey." It was a kind of Euro-disco dance hit, and somehow it turned into "New Year's Day."

BP: What else were you listening to during those formative years?

AC: I was drawn to things I thought were either sexy or aggressive -- or both. I

really liked the violence of what Jean Jacques Burnel was doing on the first couple of Stranglers records. He had this mighty

sound of his own, but it was also mixed with their keyboard player's Hammond organ bass for a very interesting effect. And

there was Bruce Foxton of the Jam and Joy Division's Peter Hook, and of course Paul Simonon of the Clash. His playing was

more sexy than violent, plus it was a bit more dubby, which I wasn't fully tuned into at the time.

Later on I got in to the classic Bob Marley records with Aston Barrett. I always

liked the position the bass took on those records, as opposed to the position the bass is usually given. Same with John Entwistle

-- he plays remarkable stuff that can be hard to follow, but I love that he refuses to be put in the background.

BP: Is it true you were U2's musical leader in the beginning, back in the late

'70s?

AC: Perhaps -- but that's only because punk rock had just happened, so it wasn't

really important that you knew how to play so long as you had some equipment [laughs]. I'd simply decided I was going

to be a musician, so I got this Ibanez copy of a Gibson EB-3 and a Marshall head, and I guess those crucial ingredients made

the others figure I knew a bit more about music. I did know a thing or two about my equipment, but I certainly didn't know

anything about playing.

BP: What were the band's goals in those days?

AC: The ambition was just to end the song together! We had these interminable rehearsals

where we would never actually get to the end of the song. But we also wanted to be part of what we felt was going on. In terms

of musical values, it was a time of throwing off the idea that people who played guitars in bands were these rock gods who

were to be obeyed and saluted. We got off on the idea that you could play a three-minute song with a few basic chords as fast

as you possible could, and that was a good enough reason to be onstage. It meant that you had a life right now -- that you

didn't have to spend three years in your bedroom trying to figure out how to play "Stairway to Heaven."

BP: Your playing got a lot groovier later on, starting with 1988's Rattle and

Hum.

AC: That may have been me getting lucky in a way. It's always depended on the tune

with us, so as our songwriting became more developed and there were better chord progressions, I found I would fall into more

interesting things. I wouldn't literally know where I was headed when I started out, but Larry's drums have always told me

what to play, and then the chords tell me where to go. Because of this, my parts are very much created as the song is evolving.

BP: Does the whole band compose this way?

AC: We do write in an unconventional way, I suppose. If we try to arrange a song

that's already been worked out on acoustic guitar, it's hard for us. But if we start with a few bits and then work around

each other to develop the song, we seem to go to more interesting places. "Bullet the Blue Sky" is a great example; it's really

just one musical moment, extended in time. Larry started playing that beat, and I started to play across it -- as opposed

to with it -- while Edge was playing something else entirely. Bono said, "Whatever you guys are doing, don't stop!" So we

kept playing, and he improvised that melody. "Please" [Pop] was another happy accident. One of our producers, Howie

B., was playing a record in the studio, and I started to play a bass part over the recording. It created these strange grooves

and keys, and my line really began to work only after Howie stopped the record.

BP: How important is your three-piece lineup to this free-form approach?

AC: Three pieces can be limiting, but there's something to be said for learning your

chops as a three-piece. If you can hang together that way, it becomes easy to know if the instruments and people you're adding

on top are right or not. I'm grateful this was never a band with a keyboard player and another guitar player, because then

what chops would I have ever needed?

Still, we've almost always augmented our records with keyboards and other things.

We got a lot of attention with the Pop record, since we'd all become very interested in club music and computer-generated

loops. But those were things we'd been using pretty much from Unforgettable Fire onward. Lots of bands in the late

'90s were saying, "We use the studio as an instrument" -- but we were doing that with Brian Eno as early as 1984. It's not

that we don't like what U2 does naturally; it's just that we sometimes want to stretch what U2 can be, and where it can go.

BP: Unlike much of U2's '90s work, the new record is quite stripped-down.

AC: We came to All That You Can't Leave Behind feeling that the unique thing

about U2 is the very thing we do when we get together. That sounds vague, but the idea with this record was to look at the

band itself, and to realize that is our strength -- that's what nobody else has. So as a consequence the songs on this record

are very stripped down. Everyone simply contributed the essence of what they've always done. For my part, it was about finding

what was necessary to get the song right, and not consciously looking for any "Wow!" moments. In fact, in several cases we

simply kept performances that began as demos from when we began writing for this record, almost two years ago.

BP: Does past U2 music ever get in the way of new U2 music?

AC: For us there's U2 music, and then there's everything else. And between records,

we listen to the stuff that interests us; we really don't listen to much U2. We're always re-establishing the fact that we

share musical tastes in the same way we did 20 years ago. The music we like now may be different from what it was then, but

our shared tastes give us a way of judging things we can still trust. So if everyone in the band is saying they don't like

something, you know why, since you know their frame of reference. And every time we make a new U2 record, we bring along that

frame of reference.

BP: What has it been like to play with Larry for over 20 years?

AC: After we'd been together a couple of years and we were doing our first record,

people were talking about Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts having played together for 20 years. Everyone was saying they must

really have it down -- but I remember thinking, what are you talking about? At that time I didn't appreciate what they did

at all. Now I appreciate it much more. When you've been playing with the same group -- and particularly the same drummer --

for that amount of time, you don't really need to talk too much about it; you just do it. So in some ways it's gotten simpler

over time, and in some ways I'm less reverent about my parts. You don't worry as much; you just know you don't have to overplay.

BP: You still have a way with a simple part. The eighth-note line in "Beautiful

Day" changes feel throughout.

AC: I'm sure it does! That's probably Larry making me sound good. When we put that

track down I was actually intentionally not thinking too much about it. I wanted to just go with it, because it is really

a basic eighth-note part. Sometimes when I'm playing, I get to a place where the bass seems to find its own rhythm, and then

it becomes just a matter of which notes to push and which ones to hold back on. It's a discipline, really.

I once read an interview with Tony Levin where he said, "I'm a bass player -- I like

doing the same thing over and over again." And that's exactly it, you know? For me, that discipline comes from years and years

of playing with Larry, and knowing he has a certain rhythm, and certain ways of producing his sound. Our two approaches just

get mixed up into one.

BP: Are you still playing your '72 Precision?

AC: I am. It's got a bit less varnish than it once had, but it's still around. I

see photographs of it from different tours, and I can see the varnish gradually wearing off. It's a really light instrument,

which is fantastic, because it's got this nice brightness without losing any bottom end. I'm always changing something on

it, but it's still pretty much the same instrument I've always played. I did put a Jazz neck on it very early on; I find the

Jazz neck suits my left hand better. The Precision is a painful, physical thing to do battle with. The Jazz is a bit more

ladylike.

BP: You've also played some odd custom basses over the years. What do you listen

for in a bass?

AC: I like a clean top end that can cut through, but I also like a big, air-moving

bottom. The Precision has always given me that, so the custom basses I've used have always been selected because they complement

my Precision. That big yellow thing -- the banana bass -- that I played on the Pop tour is a great-sounding example. It was

made by Auerswald, the German guy who makes Prince's guitars.

Recently I've actually been playing Jazz basses, though, because I've been using

my fingers a lot more, and I've been after a bit more definition. I recorded the new album with two Jazz basses -- a '61 and

a '72. I also used my old Gibson Les Paul Recording bass. It's a short-scale thing with this great, round bottom that just

moves air. It's great in the studio.

BP: You've always blended a direct line with a miked SVT rig, but this record

sounds different.

AC: This time around I was after something that sounded good at really low volume.

I'd like to say it's about tone, but it might just be age [laughs]. So I recorded with an Ashdown 800 head and the

matching cab with two 12s and one 15. Also, we moved around a lot in the studio this time, trying different rooms and all,

so I used an Ashdown 400 4x10 combo, too. Occasionally we'd add extra bottom end with a dbx 120XP Subharmonic Synthesizer

-- but these days I don't much. I've come to prefer the pure, clean sound of the bass. I like the physical effect of a good

bass sound; that's really what it's all about. And that's why the best place to stand when you see a band is always in front

of the bass rig!

BP: Which lines on the new record have this effect?

AC: "In a Little While" and "Elevation" both have that physical bass punch. I always

think the bass should be much, much louder on songs like that. They're both fairly simple in terms of structure and chords,

but the bottom end is moving, and that's what's beautiful. "Kite" is another line that, although it's basic, seems to really

talk.

BP: After all these years, what are the best and worst things about being U2's

bassist?

AC: Sometimes we get photographed a bit too much, and for the wrong kinds of papers

[laughs]. You feel like saying, "I just play bass! You don't need me in your paper!" But it's a celebrity culture,

and we don't suffer for it too much. We're good at hiding behind music, but sometimes people do get excited for the wrong

reasons.

As for the good parts, we've got great fans. They follow us through all sorts of

changes, and in many ways they encourage us to continue pursuing music that excites us. But the best thing really is that

I get to hang out with three friends and musicians. And if I get stuck, in whatever way, I've got three guys who are willing

and able to help. That's a great thing.

© 2000 Bass Player. All rights reserved.

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||